|

||

| . . . Chronicles . . . Topics . . . Repress . . . RSS . . . Loglist . . . | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| . . . 2024-02-13 | ||||||

Terry Bisson's voice tended tenorish with a crackled glaze, but sturdy, rooted somewhere around baritone. A Border State blend of drawl and twang, more trawl than Drang, but with firm outlines drawn around each word. A good voice for reading verse, spinning yarns, cutting to the quick, quiet encouragement, or curt exasperation. (I treasure his outburst against Elizabeth Bishop's anti-petroleum bigotry.)

Like Border-Stater Mark Twain, he kept a straight face; I often saw him amused but don't remember his laugh. Other things I don't remember: bullying, blather, bluster. Terry's provocations were strictly balanced by his silences: he was good at observing and listening and calling a halt.

Anyone so closely allied with Black Panthers and Weathermen and the Grand Old Communist Party would learn early to keep their trap shut. By the time I met Terry his politics were no secret but he still refrained from preening or point-scoring; he liked to declare a lifetime habit of voting Democrat. Although we never talked about it, I'd guess his restraint came natural, or at least came to fit him comfortably. Terry might be certain that feckless softies like me would go up against the Revolutionary walls, but just as certain that a whole lot of fellow freedom fighters would too. As the poet sang, "If there's a hell below, we're all going to go." Nothing to gloat about, just something to come to terms with — something that set the terms.

Whether that's a fair description or not, Terry's company felt genuinely benign. I never met a more reliable medicine for misanthropy.

| . . . 2023-10-25 |

I and my brother lean socialist because we were raised Navy. Shelter, health care, and education were government-provided, race-'n'-class distinctions were government-muffled, and it all left us better off than our socioeconomic peers stateside.

Since our childhood, stateside's only gotten harsher; the forces of Counter-Enlightenment raze public schools and public libraries with particular enthusiasm. And so I was happy (relatively speaking) to read that some military budget still diverts toward the old collective dream.

In a world of shortages getting shorter, I thought we at least had an adequate supply of glib bullshit. Where we could use automated assistance is cutting through it.

But that would require more than parroting a text database or comparing citation counts. It would require flexible and yet clearly explicable notions of "trust" and "validity" and "likelihood"; it would require breaking into the fortress-tomb surrounding a century of research and creation; it would require continuous expenditure and acknowledged fallibility. It would not profit our rulers; it would disappoint our consumers.

No, glib bullshit is what rulers understand, what consumers consume, and so it's what our exciting new-and-improved factories produce. Since it's all we've got and all we're getting, can these new sources of deceitful mimicry be put to less redundant use?

Possibly. Context-sensitive translation 1 is difficult, unrewarded, therefore in short supply, and bullshitting at its most benign: false reassurance is the goal.

1. I emphasize context after witnessing an application's elegantly varied renderings of "Erster Aufzug", "Zweiter Aufzug", and "Dritter Aufzug" as "First Lift", "Second Hoist", and "Third Elevator".

Prescription (courtesy of Dr. Shazeda Ahmed): Take one dose of "The Fallacy of AI Functionality" after every exposure to five or more AI-hypes.

| . . . 2023-06-30 |

(Written for Jonathan Gibbs's "A Personal Anthology Collaborative Summer Special 2023".)

With all due respect to late-February Boston, summer’s the season I dread: in childhood the season of boredom; in early maturity, of physical assaults, desertions, and extremely bad decisions. I’m fish-belly pale, with one carcinoma already knifed out, and even ten minutes at 29°C are enough to begin scooping gray matter from my dutch-oven skull and reduce me to a monosyllabic zombie shambling more or less in any direction you lead.

If my most memorable warm-weather traumas had been triggered by mechanical rather than organic failure, Alfred Bester’s ‘Fondly Fahrenheit’ would be the seasonal selection.

Instead I thought of this stripped-down barely-a-story, simple enough for even the sun-addled to follow. In the summer an upwardly mobile Manhattanite’s fancy turns to thoughts of a Westchester County home — ‘white, with a lawn, with grown-up trees’ — which proves one egg too many for his juggling to handle.

Highsmith was a diagnostician of gender roles, generally presenting the threat of physical violence as a comorbidity of maleness. But, as ‘Blow It’ demonstrates, the Highsmith-male trinity of presumed competence, prescribed sense of agency, and near-absolute absence of rational motive doesn’t need bloodshed to generate recognizable nightmares. What say let’s climb out of these sweaty clothes and into a dry martini?

I long ago concluded that earworms are the only disease treatable by homeopathy, but on re-reading that short short-story recommendation, I notice for the first time that the traumatic midsummer triumvirate of "physical assaults, desertions, and extremely bad decisions" has a pinch of something in common with my solstitial reading of choice.

| . . . 2023-06-20 |

"No flesh! No flesh! È la mia casa!" — Priest to tourist, Florentine church, 1989

"Again and again and again and again" — Lou Christie to the world, 1965

Email from the University of Chicago Press promoted the sort of philosophy book I don't normally seek out. But for one reason and another, it caught my attention:

It seems to me that instead, the moments of angelic clarity tend to overrepresent themselves in my mind. It seems to me that a person might be tempted to live by these moments too much; one might hold too hard to them, wanting to have scales forever falling from one’s eyes and lightning forever striking. [...] It can be good to attend to moments of passion, clarity, revelation, ecstasy, discovery. It can be good to listen to warnings. But it is in the nature of these moments to slip away. Lightning flashes are brief. In any attempt to bind these moments, there is a risk. These attempts can leave us living by and bound by something, yes, but not by the surprise that broke over us once; by, instead, an impoverished version of that surprise: less threatening, but also less nourishing. As the psychoanalyst and philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle writes, “this is perhaps the danger of ‘eventness’; the temptation would perhaps be to outsource the process, to posit the most perfect horizon possible, to recreate the whole protocol, the conditions of the happening of the event, and thereby, in fact, essentially to repress it.”— On Not Knowing : How to Love and Other Essays by Emily Ogden

(Or, as Stephen Dedalus would punctuate it, On Not Knowing How to Love, and Other Essays.)

An occasional glimpse at the memory of the flash of enlightenment or trauma can serve as touchstone or reminder, but staring at it fixedly makes it the seed of a black spot that obscures the original moment and grows to obscure everything around it. The time leading up to it was a waste of life because the flash hadn't yet happened (or because it wasn't avoided); the time after it is a waste of life because of all that was lost by its not happening sooner (or was lost in its happening); the flash itself is demeaned by the worthlessness of the life it changed.

This might contribute something to the notorious reluctance of wartime survivors to volunteer accounts of their so-fascinating experiences, as well as the near-universal tendency of revelation to shift into proselytizing and ritual, or to screw into increasingly desparate rebirthagains. In a comic register, the Dedalus-patented alternating current of "soaring in an air beyond the world" and "Oh cripes, I'm drownded" is grounded by (grinds into) the daily highs and lows of the working novelist.

That leveling away from (uplifting or negatory, peak or abyss) enlightenment to routine, chores, collaboration can be described either as a retreat and a betrayal or as a fulfillment and a tribute. At any rate, earthbound but no longer buried and not yet buried. If Apollo's missing lips whisper "Change," its torso broadcasts "Persist."

Not that many people are likely to seek advice from a headless limbless torso on a plinth. Or from me, for that matter.

| . . . 2023-06-16 |

Months of Dante reading left me in a conjunctive mood. But Gian Balsamo's rubber biscuit repulsed my age-brittled jaws, and while James Robinson's Joyce's Dante: Exile, Memory, and Community hit some exhilarating high points, the ratio of insight to overreach fell short of full satisfaction.

Instead, tops in Joycean reading this year was Andrew Gibson's The Strong Spirit: History, Politics, and Aesthetics in the Writings of James Joyce 1898-1915, a prequel to his fine twining of Ulysses with Irish politics, and even finer by dint of its longer duration, less familiar material, and triple-storied structure — Irish politics at the time Joyce wrote and Irish politics at the time of which Joyce writes, with Joyce's work to bind them — which counterintuitively made the recursive knots of Irish history easier to follow than a straightahead chronicle would. Garnish with fresh-ground peppery defenses of Stephen Dedalus's honor and Exile's worthiness.

Gibson's Exile chapter-and-championship delivered engaging history; still, I'm not yet willing to re-enter the turf-colored stale-urine-scented ditch of the play itself. But he did make me wonder how my reaction to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man might have changed since my last full reading, and how scholarship might have changed since my ancient used paperbacks of the novel and Don Gifford's Joyce Annotated were published.

The University of California libraries own no copy of the Gablerized edition, since it never appeared as an exorbitantly priced university press book. (For the same reason, they lack copies of the most interesting scholarly editions of The Way of All Flesh and Vanity Fair.) However, Jeri Johnson's post-Gabler notes for the 2000 Oxford paperback resolved a long-standing curiosity as to why Baby Tuckoo pronounced the "r" of "green" but not of "rose"; her introduction did me the further favor of pointing towards my even more ancient used paperback of James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses by Frank Budgen.

I'd come to think of the Budgen as one of those publications which exist largely to publicize and excerpt otherwise inaccessible work. Unfair! Budgen sustained a respectful but not sycophantic and almost comfortable friendship with Joyce longer than nearly anyone else managed, he supplied much of Joyce's most quoted table-talk, and, as Johnson says, his mini-Lacoön is suggestive and useful. In my instance, it usefully soothed my occasional wish that the streamlined-for-Bildungsroman stereotyping of Dedalus had been scuffed a bit by young Joyce's real-world athleticism and singing career: Rembrandt portrayed himself holding paintbrushes rarely, but canal-jumping never.

Joyce said to me once in Zürich:

"Some people who read my book, A Portrait of the Artist forget that it is called A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man."

He underlined with his voice the last four words of the title. At first I thought I understood what he meant, but later on it occurred to me that he may have meant one of two things, or both. The emphasis may have indicated that he who wrote the book is no longer that young man, that through time and experience he has become a different person. Or it may have meant that he wrote the book looking backwards at the young man across a space of time as the landscape painter paints distant hills, looking at them through a cube of air-filled space, painting, that is to say, not that which is, but that which appears to be. Perhaps he meant both. However, it led me to ask myself if the writer, representing his own past life with words, is subject to the same limitations as the painter representing his physical appearance with paint on a flat surface. How near can each one get to the facts of his own particular case? Their limitations cannot of course be the same, but they are equivalent, and on the whole, the painter has the lighter handicap and is the likelier of the two to produce a true image of himself in his own material, although the extra difficulties that confront him are considerable. His first limitation is the inevitable mirror. The best of quicksilvered glass gives an image that is less true than an unreflected one, and the size of that image is by half smaller than it would be, were the same object standing where stands the mirror. He sees in the mirror a man holding in his left hand brushes and in his right hand a palette and he paints righthandedly this left-handed other self. Then he is fatally bound to paint himself painting himself. His functional, his trade self is in the foreground. The strained eye, the raised arm the crooked shoulder may be ingeniously disguised (they generally are) but something of objective truth gets lost in the process. And he is not only painting himself painting himself; he is also painting himself posing to himself. He is painter and model, too. The painter may be pure painter, but the model may be a bit of a poet or half an actor, and this individual will slyly present to his better half's unsuspecting eye something ironical, heroic or pathetic, according to the mood of the moment or the lifetime's habit. The limitation of viewpoint is obvious. The painter's two-dimensional mode of presentation limits him to one view of an object whatever he paints. He chooses that view and must abide by his choice. All that he can do is to convey the impression in painting one side of an object that the other side exists. In the case of any other object but himself he has at any rate the whole compass to choose from. He can walk round any other model but not round himself. So that, unless he resorts to one of those cabinet mirrors in which tailors humiliate us with the shameful back and side views of our bodies, he can see nothing of himself but full face and three-quarter profile. All this has to do merely with the getting to grips with what is usually called nature. The resulting picture, as all the galleries of Europe testify, may be as good as any other. Are there any Rembrandts we would change for the best self-portraits? One difficulty or limitation more or less among thousands is of no consequence.

And the writer's self-portrait? Goethe subtitled his own, Dichtung und Wahrheit. Did he mean that he consciously mixed fiction and fact to puzzle, delude or please, or did he mean that some Dichtung would be there by sleight of memory or because there were many true things better left unsaid? All the psychological inducements to fictify his portrait are present in greater measure for the writer than for the painter. A painter will rather paint the wart on his nose than the writer describe with perfect objectivity the wart on his character. All the posing that the painter does for himself the writer must do also. If he has a passion for confession he will exaggerate some element or other — make the wart too big or put it in the wrong place. He has his favourite role too — villain, hero or confidence man — and he would be more than human if he failed to act it. But, worst of all, his medium is not an active sense, but memory, and who knows when memory ceases to be memory and becomes imagination? No human memory has ever recorded the whole of the acts and thoughts of its possessor. Then why one thing more than another? Forgetting and remembering are creative agencies performing all kinds of tricks of selection, arrangement and adaptation. The record of a man's past is inside him and there he must look with the same constancy as the painter looks at his reflection in the mirror; only he is not looking at something (still less round something like a sculptor) but into something, like a mystic contemplating his navel. He can as little walk round his past life psychologically as the painter can walk round his reflected image. Between the moment of experiencing and the moment of recording there is an ever-widening gulf of time across which come rays of remembered things, like the rays of stars long since dead to the astronomer's sensitive plate. Their own original colours have been modified by the medium through which they passed. The "I" who records is the "I" who experienced, but he has grown or dwindled; in any case, he has changed. The continuous present of the painter is the writer's continuous past. No doubt, the most fervently naturalistic painter paints from memory, for there is a moment when he turns his eye away from the scene to his canvas and he must remember what he saw, but for practical purposes his time may be regarded as present time. Interpretation in material, words, pigment, clay, stone, is equivalent in all arts and all have the same aesthetic necessities. One other thing: if the writer cannot see the other side of himself, by a still more elementary disability he cannot see the outside of himself in action at all. He knows what he does as well as any, and why he does it better than any, but how he does it less than any.

Does he even, for example, know the sound of his own voice? If he is a singer he may, after long practice, get to know the sound of it when he is singing, but he will certainly not know how it sounds when he is arguing with a taxi driver. He knows the inside of himself and the outside of everybody else. He supplies other folk with his inner experiences and motives, and himself, by judgment and comparison, with the visible outward of their actions. The mimic among our friends will show the assembled company how we walk or talk. It seems strange and unbelievable to us, but from the laughter and "just like him"s of the others we know that it must be reasonably like. The essence, however, of this comparison is to show that all self-portraits, whether painted or written, are one-sided — that they are pictorial in character, not plastic.

Stephen Dedalus is the portrait and Bloom the all-round man. Bloom is son, father, husband, lover, friend, worker and citizen. He is at home and in exile. [...]

Rodin once called sculpture "le dessin de tous les côtés."; Leopold Bloom is sculpture in the Rodin sense. He is made of an infinite number of contours drawn from every conceivable angle. He is the social being in black clothes and the naked individual underneath them. All his actions are meticulously recorded. None is marked "Private." He does his allotted share in the economic life of the city and fulfils the obligations of citizen, husband and friend, his body functioning meanwhile according to the chemistry of human bodies. We see him as he appears to himself and as he exists in the minds of his wife, his friends and his fellow citizens. By the end of the day we know more about him than we know about any other character in fiction. They are all hemmed in in a niche of social architecture, but Bloom stands in the open and we can walk round him. [...]

His wife, Marion, is a onesidedly womanly woman.

– Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses

| . . . 2023-06-06 |

George Crabbe and Thomas Moore’s The Fudge Family in Paris (1818) are exponents of the same realistic tradition, but one that is applied with a new degree of perfection to narrative poetry. [...] Thomas Peacock’s Headlong Hall (1816) and Nightmare Abbey (1818) are also long narrative poems. As pastiches on the gothic novel, their satire relies on the presence of realistic detail. Peacock and the other poets show that realism and verisimilitude are not the same.- "James Joyce and the Middlebrow" by Wim Van Mierlo,

New Quotatoes: Joycean Exogenesis in the Digital Age

ed. Ronan Crowley & Dirk Van Hulle

| . . . 2023-05-12 |

My most pleasant memory of "Elizabeth Episode II - The Empire Gives Up" is her performance as top sullen husk in this BBC production, a satirical documentary more scathing than its competition because none of its makers were in on the joke (video editor possibly excepted). If you're unsure whether to accept or refuse an O.B.E., the investiture sequence should decide you: a cross-section of British society as exhibited by Damien Hirst. Stay awake for a memorable cameo by America's own hollow rat-infested figurehead, Ronald Reagan.

(My most pleasant memory of its "Elizabeth II Fun Estate Sale" sequel is Kevin Boniface's characteristically brilliant "HM Queen Elizabeth Has Died".)

| . . . 2023-05-06 |

| . . . 2023-04-27 |

In youth, poetry and fancy prose styles were my best entertainment values. I didn't have to scrape up the cash for subscriptions consisting mostly of throwaway ads, or LP box sets and a constantly upgraded quadraphonic hi-fi system, or season seats in arenas or concert halls. I could lazily, at my own pace, check books out from the library, occasionally buy cheap paperbacks, and that was that.

Well, as the poet sang, "I ain't gonna be eighteen again, I know it." After the harrowing of browsable paper volumes from public library shelves, and the deforestation of used bookstores, and a series of copyright enclosures around any edition less than a century old, attaining a taste for poetry might be as expensive a prospect as it was in the years of parchment.

But wait! There's hope! Or at least an opportunity for massive corporations to leverage artificial scarcity to extract high profits from publicly funded institutions, which five out of five politicians agree is even better than hope. Ask your publicly funded institution about ProQuest LION (short for "Literature Online", in the sense of "Roach Motel"):

Right now, the subscription packages Proquest and Ebsco offer may sound like they cost a lot (between $500-$800,000 a year), but the price is “extremely low relative to the number of books acquired,” to quote the CSU report on the e-book pilot project.

The report understated its case. ProQuest doesn't merely acquire "primary texts"; it augments them. First it rips all the pages out of a book, discards some, and shuffles the rest. And then it defaces each past the point of easy readability. Imagine how much you'd have to pay a mob of Republican goons for that kind of service.

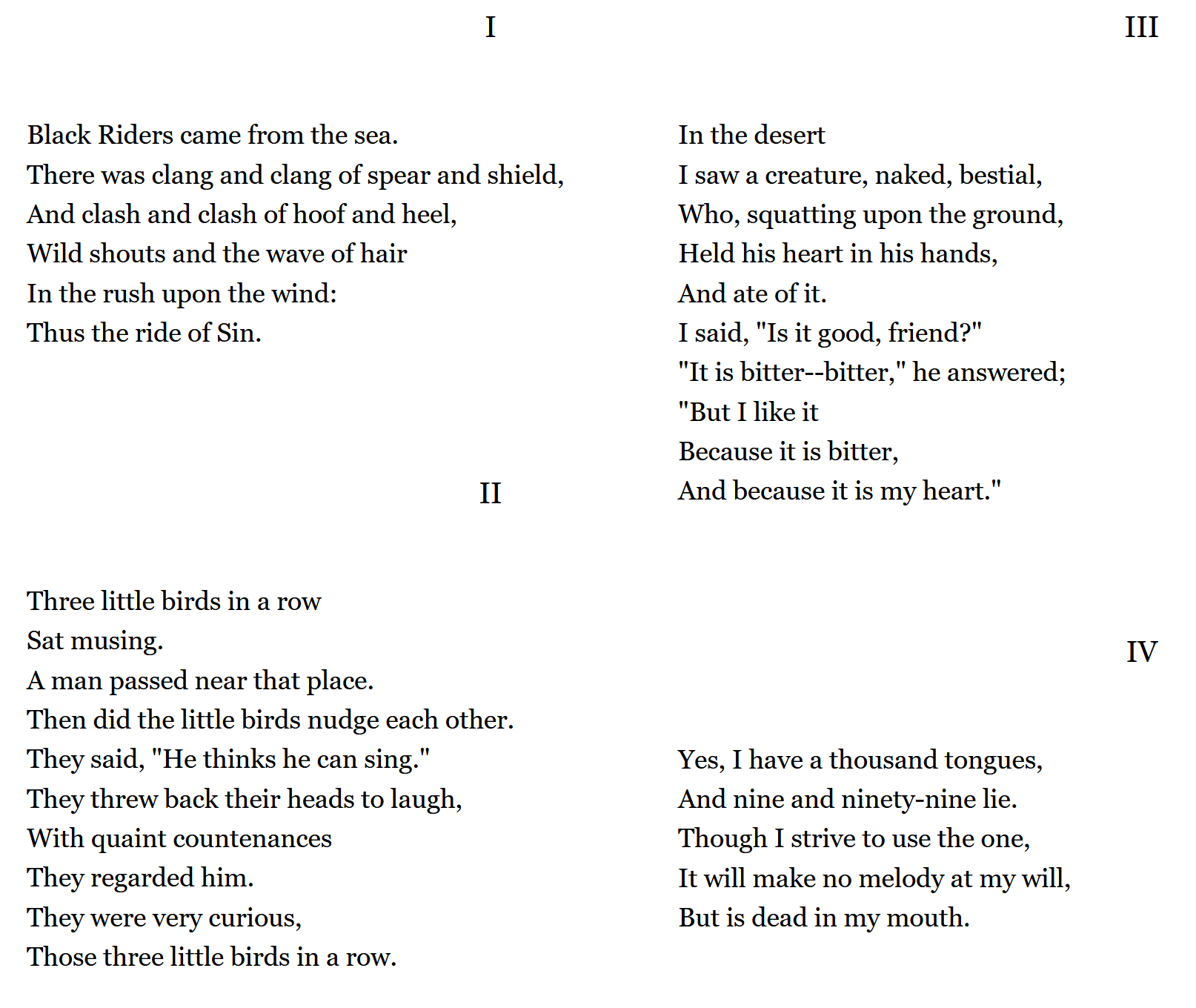

The damage is hardest on otherwise unavailable poetry, of course, but since I don't want mean old Mr. Hachette's gang coming after me I'll illustrate from the public domain: Stephen Crane's first collection of peculiar versicles, The Black Riders, and Other Lines.

The Hachetted Internet Archive still provides a facsimile of its 1905 edition:

Project Gutenberg has well-OCRed HTML and EPUB versions:

ProQuest sources the poems from a scholarly edition (shorn of all scholarly apparatus) but the contents match:

![Contents: 136 items, beginning with [I. Black riders came from the sea]](images/Proquest-Crane-contents.png)

So we just need to select the first batch, download a PDF, open it, and start reading:

![Huge gobs of boilerplate noise around number-prefixed verse sections, beginning with [XIX. A god in wrath]](images/Proquest-Crane-first-poems-in-PDF.png)

After many tries over many books, all I can make of ProQuest's ordering algorithm is that it resolutely ignores page numbers.

Line numbers, on the other hand! A Comp. Sci. major must've opened their Norton's anthology, seen familiar digits unobtrusively appended at a polite distance every five or ten lines, and decided those were the best parts. Words are afterthoughts.

ProQuest's save-&-export options include "Text only", which sounds promising but looks like so:

![Huge gobs of boilerplate noise around number-prefixed verse sections, beginning with [XIX. A god in wrath]](images/Proquest-Crane-first-poems-in-text.png)

Not much gained, except for gluing the title to the first line of verse.

To wax professional for a moment, there's no Javascript task more basic than toggling the visibility of a particular sort of text. And if memory serves me well, when I first encountered "LION" twenty-or-so years ago, a button was provided to remove those numbers. Nevertheless, at some point some unknowable dysfunctionary, presumably tasked with adding more boilerplate branding and fuckall else, learned it wasn't worth the effort.

Must be fun for screen-readers.

Now, I'm just a simple country boy who won a library card in a Bingo game, not a department head, nor an emeritus doctor of physic nor philosophy, nor a donor ripe for money-debagging. But maybe somewheres up thar in the whirly starry spheres, someone with actual influence actually gives a shit about getting something useful from their investment?

| . . . before . . . | . . . after . . . |

Copyright to contributed work and quoted correspondence remains with the original authors.

Public domain work remains in the public domain.

All other material: Copyright 2023 Ray Davis.